Let's Look at the United States' Nuclear Policy

Nuclear exchange is not a good thing. And if it happens it may not wipe out everything.

This was originally written on March 12th 2022

TL:DR; Nukes are a bad thing. A nuclear exchange would not destroy the human race. It would not cause a nuclear winter (but probably some other climate disaster). It would not necessarily destroy one government or another. It would not destroy capitalism (sorry posadists). It will bring a lot of things to a standstill. And life is going to suck.

You may have been seeing this map1 of nuclear targets floating around the internet in the past month.

This map is wrong. It is claimed to be from 2017, but it is actually from 2002. It was compiled by an anti-nuclear group using data from the middle of the Cold War.2 People today who have served in the armed forces since Iraq may have noticed the problems with it. Many of those targets no longer have any military presence whatsoever. That base in Wisconsin is housing more termite colonies than plane parts now. The majority of those silos have been de-commissioned. The strategic plan for nukes doesn’t look anything like that anymore. If you just like looking at scary maps, this one3 compiled from data from FEMA and Wikipedia is somewhat more accurate.

There are a lot of misconceptions and myths about nuclear warheads. I’m going to try to explain how nukes are used today. It is sadly extremely relevant to right now. I tried to not make it dull reading. There’s some science in the beginning which is important to understand. There is history in the middle which you can skip if you don’t care. And then there is what is happening right now at the end.

“Tell me the difference in the number of people I’m going to kill.” Bush said in a calm, no-nonsense tone to Dick Cheney. It was November 8, 1990. The Soviet Union was crumbling and George H. W. Bush had just announced a doubling of troops for the operation in Kuwait. He had just received a briefing of four distinct nuclear major attack options. I'm going to stop here before it gets too juicy. Let’s jump back to why a conversation like this is happening, and how it may be happening again at this very moment, right now.

What a Nuke Is and What it Isn’t

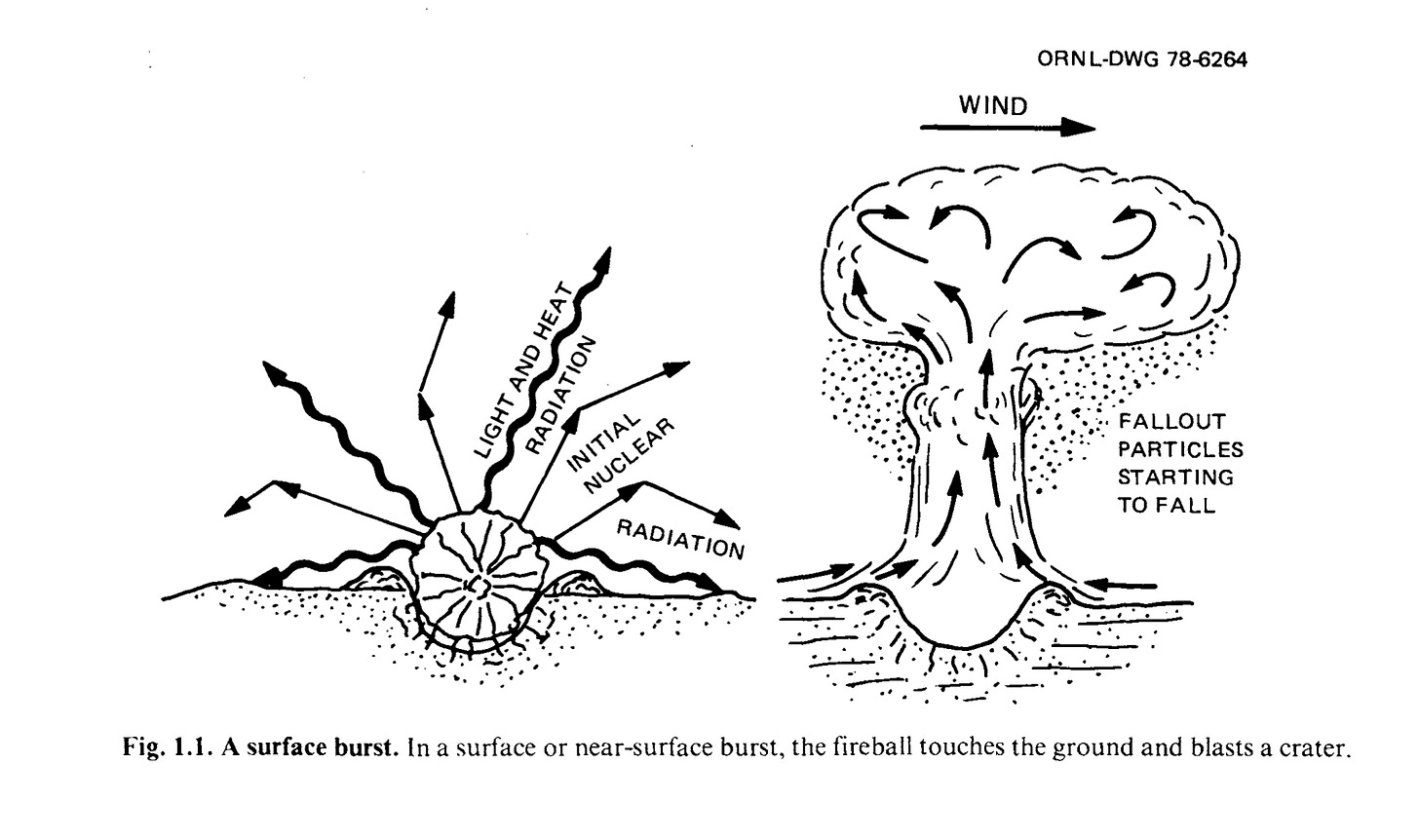

There are two ways a nuclear strike (or any artillery, really) goes off at a target: a surface burst or an air burst. With a surface burst, a nuclear weapon explodes near enough to the ground that its fireball touches the ground and forms a crater. Thousands of tons of earth are pulverized into trillions of particles. These are radioactive particles that go up in a mushroom cloud for miles and then fall back to the earth. This is called fallout. The wind can carry these fallout particles for tens or thousands of miles before falling back to earth. The biggest ones deposit in a few hours, but the tiniest ones can stay airborne for weeks to years.

An air burst is different from a surface burst in that the fireball does not touch ground, and therefore there is no crater. This also means it only makes extremely small radioactive particles which stay in the air for days or years until they are brought down by rain or snow. An air burst has the additional danger of an increased blast effect. Thermal pulses of heat and radiation will travel farther than its near-surface counterpart.

Now let’s kill some myths.

Fallout does not immediately give you cancer. Radioactive decay eliminates that danger with time. The half-life is the time it takes for any given quantity of a substance to react, or decay in this case. For example, the half-life of strontium-90 is 28.8 years. If we started with 10g of strontium-90, only 5g would remain after 28.8 years, and then 2.5g would remain after another 28.8 years and so on. Fallout is measured by dose rate in roentgens (R) per hour. About two weeks after the explosion (depending on proximity to the center), if a person has been sheltered and not exposed to fallout, then they can safely go outside as the dose rate has fallen from 1000 R/hr to less than 5 R/hr. There were higher rates of cancer and birth defects in Iraq among the people victim to the depleted uranium munitions that the United States used than among the people who survived the Hiroshima bombing.4

Gamma radiation does not penetrate everything. 18 inches (45cm) of packed earth will reduce the level of radiation you receive to that of a medical X-ray. The denser the substance, the better it serves for shielding material.

Nukes do not set everything on fire. On a clear day, a 1 megaton explosion can cause second-degree burns on people exposed as far as ten miles away from the center of the blast. On a heavily cloudy or smoggy day, the moisture or particles in the air absorb or scatter much of that heat. So much that the area endangered by the fireball could be less than that of the severe blast damage.

There will not be a nuclear winter. Nuclear winter is a discredited theory put forth by anti-nuclear groups since 1982. It is far more likely that a different ecological disaster will occur from a nuclear exchange. However, I will not get into all the science of it here.

A nuclear exchange is not the end the world, or the end of human life. In fact, the government’s greatest concern with a nuclear exchange is that people will no longer want to do wage labor. Either from the physiological effects caused by sheltering for the necessary amount of time, like what we have all seen in the COVID pandemic of 2020, or from being so beyond done with the people in power who just snuffed out tens of millions of lives in a couple of hours. Or some combination of those things. Regardless, the exploiter class would be in great danger. That is what worries the government more than anything.

Nuclear Strategy

Now that we no longer see nukes as instant global annihilation devices, lets see how the people with the power to use them planned on doing so. It boiled down to a few key points:

Keep my country alive. There must be continuity of government or there is no point.

Remove the enemy’s ability to kill my country. And if possible, their ability to reform for a counterattack.

Make sure my country is thriving afterward. This means minimizing damage from the enemy and protecting my economy and society.

To reach those points the targets can’t be cities, like Nagasaki and Hiroshima. The most important targets in a nuclear exchange are other nuclear warheads. After that (or before that) is stopping the enemy’s ability to launch nukes. That means heads of government locations (like the national capitol), and communication nodes used to transmit orders. Following that are military targets. Like air force bases, fuel depots, munitions factories, power plants, and so on. Cities, and even “urban industrial” zones, are at the bottom of the list. Nukes are too important and valuable to waste them on that.

From here we can figure the less abstract rules of engagement. Whoever runs out of warheads first, or loses the ability to issue timely commands to those warheads, completely loses the exchange. Therefore, if one side starts losing or looks like it is going to lose there is more pressure for them to sue for peace. This actually cuts both ways, because if tensions blow over and the winning side completely dominates and the losing side has no chance of recouping losses, they may flip the table. This is where the idea of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) comes from. If the loser can’t hope to save its military targets or keep up with the opponents military targets (meaning they can’t satisfy point 3), then they may just go for “killing”. Bring the enemy down with them: hit non-military targets like mass population centers. If I can’t win, no one can.

One last bit of math. A nuclear warhead is not guaranteed to be successful. It could go off course, missing the target by a couple of miles. It could be a dud and fail to detonate. It could get intercepted or shot down. It could fail to destroy the target – that being an enemy launch site or key military node. Nuclear equipped countries bury their silos pretty deep for a reason. Let’s say with those factors there is a 75% chance of a single nuke successfully launching, traveling to, detonating, and destroying the target. If we up that to three nukes for a single target we get a 90% success rate. Adding any more nukes is diminishing returns and a waste of warheads.

What Changed Between Hiroshima and Now, like to Right Now

The United States’ nuclear policy obviously didn’t start tactical. It was 12 years after we dropped the Fat Man and the Little Boy when the Air Force’s think tank, the RAND Corporation, weighed in on the Pentagon’s nuclear ideas. In 1954, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, brother to Allen Welsh Dulles who was the director of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS, what turned into the CIA), called for “massive retaliation” against the Soviet Union for any incursion into Asia or an invasion of West Germany.5 General Thomas Power, the former chief of staff to the Army Major General during the war, particularly liked bombing cities: “Why do you want us to restrain ourselves? Why are you so concerned with saving their lives? The whole idea is to kill those bastards! Look. At the end of the war, if there are two Americans and one Russian, we win!”6 The RAND Corporation “wiz kids” thankfully changed those ideas in the following decades.

When Kennedy first got in office, it was assumed that the Soviets were cranking out nukes and would have 1000 by 1965. Intelligence from the Discover satellite proved that to be false; they barely had a quarter of that. Still, in 1962 it looked like Khrushchev was eyeing West Berlin.

There began the plan of a “first-strike”: a small nuclear attack that destroyed all or nearly all of the Kremlin’s weapons. It got rolled into the Single Integrated Operations Plan (SIOP)-62. Kennedy found it intriguing. SIOP-62 would kill 54% of the Soviet population, and 82% of its industrial buildings. In terms of risk, the American fatalities in a thermonuclear exchange were negligible at best and 70% at worst.7 This frustrated Kennedy for the following months and we settled on a policy of nuclear deterrence. If we had a ton of nukes and they had a ton of nukes, neither of us would use them because the results would be catastrophic. The Cuban Missile Crisis strained that a little bit, but ultimately undersecretary of state George Ball laid it out: The Jupiter missiles in Turkey “were obsolete anyway. I don’t think NATO’s going to be wrecked, and if NATO isn’t any better than that, it isn’t good to us.”8

By the time of Nixon’s presidency, nukes had changed and the SIOP had changed. Nukes could be launched from a silo or a submarine and in a half-hour flight time touch-down on the other side of the planet. An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM). There was no longer first-strike capability. Both countries had roughly the same number of armaments. A stalemate. “We may have reached the balance of terror.” Nixon said.9

Let’s jump ahead a bit. On Sunday night, November 20 1983, ABC aired a two-hour made-for-TV film called The Day After, a drama depicting the effects of a nuclear war on the people in and around Lawrence, Kansas, not far from a Minuteman ICBM complex. An estimated 100 million Americans watched the broadcast. There was even a post-show discussion panel which included Robert McNamara, Henry Kissinger, and Carl Sagan, among others. Weeks after the broadcast, discussions were held about the film at hundreds of churches and school across the nation. Ronald Reagan watched the film a month earlier at Camp David. He said it made him determined “to do all we can to have deterrent and to see that there is never a nuclear war.”

Reagan had anxieties about the Kremlin but he still signed a National Security Decision Directive declaring that if nuclear war broke out, the United States “must prevail”. I guess he forgot about that in his memoir, where he wrote “some people in the Pentagon who claimed a nuclear war was ‘winnable’, I thought they were crazy.”10

The following year, the British TV documentary-film Threads came out. I won’t tear through the film here, but its depiction of what happens after the nukes drop is narrow and a bit exaggerated to say the least.

However, in 1989 it became apparent that Threads was inaccurate in a different way: it was a gross underestimate of what a nuclear exchange would look like. Franklin Miller was a graduate from Princeton who became director of strategic forces policy just as Reagan signed his national security directive. In the years after, Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney noticed his expertise and granted him authorization to review the SIOP in the Pentagon. This was the first time an outsider got a chance to do this in 30 years. When he got there, it turns out the aging warmongers were planning to fling nukes at any vaguely military target. The number of nukes looked arbitrarily excessive. For instance, seventeen ICBMs were assigned to a landing strip and unloading hangar in the Arctic Circle of Russia. The location could only have been operational for half a year at best. And for the Kremlin, the 50 mile radius of Moscow had 689 warheads planned for it.11 Jesus Christ. “Overkill” was a severe understatement that had gone on for decades.

It wasn’t just Moscow but Leningrad, Vladivostok, Novosibirsk, Omsk, Tomsk. Soviet rubble was going to bounce quite a few times. The worse part is that this plan wasn’t supposed to launch 12,000 nukes all at once. It was supposed to launch only a few dozen as a “deterrent” to scare the Soviets and behoove them to deescalate. But that part of the plan would have failed immediately. It was horribly, technologically flawed. You can’t just drop a few nukes and say “let’s stop here”. No intelligence indicated that the Soviets would do anything but retaliate. And even if they did want to stop, Soviet radar couldn’t see the difference past 200 nukes. It would always look like a full-on attack and end in a full exchange.

Why so many nukes in the first place? Well, the Strategic Air Command really thought Soviet interceptors were that good. And doctrine specified that those targets needed to be destroyed with high confidence. Therefore they had to send 69 warheads to the anti-ballistic missile site near Sheremetyevo Airport on the outskirts of Moscow to make sure at least one of them got through. This is obviously insane. No defense system in history has that high of a success rate. And after the Cold War, western inspectors discovered the Soviet interceptors were worthless. They would have barely stopped one nuke. The reason for this missile spam was that the US’s war plan was based on supply, not demand.

That was the doctrine in the 60s and it hadn’t changed for decades. We were going to make a global apocalypse because some military boomers didn’t want anyone to review the plans and maybe affect their budget.

Now, we’ve reached Bush and his family’s obsession with body counts. We’ll come right back to that. Each year, as part of a program created during Jimmy Carter’s term, a group of officials from the State Department, the Pentagon, and the intelligence agencies, as well as select members of Congress, took part in a beyond Top-Secret exercise testing the procedures for “continuity of government” in case of a nuclear attack. They were flown all over the country, from one obscure military base to another, where they would actually be taken during a nuclear war, and rehearsed running a regime under emergency powers.12 But I’m going to skip that and some later tense moments with North Korea. We’re almost to the present.

While the Soviet Union was a shell of its former self, young US Senator Barack Obama joined the Foreign Relations Committee. It was usually just him and the chairman, Richard Lugar, as the only two senators in the room. Lugar wanted to make sure our nukes stayed locked up. When the USSR was no more, Lugar traveled to Russia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and Belarus to observe the dismantlement of nuclear missiles, warheads, and bombs. Sometimes Obama went with him. One one trip to Ukraine, he saw a giant ICBM being lifted out of its silo. His hosts let him take the long elevator ride down. One of the first things he saw was a guard’s desk. On the wall behind it were photos of American cities. Those cities had been the target of that missile.13

At the start of every presidency since Bill Clinton’s, a Nuclear Posture Review was required by Congress. George W. Bush’s review in 2002 declared that nuclear weapons “provide credible military options to deter a wide range of threats.” This is why nukes got smaller (relatively) instead of bigger. So as scary as Tsar Bomba

14 is, it is not tactically useful and has limited application.

The United States had at least 180 nuclear bombs in Europe by 2009, all of them ready to be carried by tactical planes.15 Vladimir Putin demoted himself to Prime Minister in 2008, and then won the presidency again in 2012. After which he began rebuilding the Russian military and modernizing his nuclear warheads. He was making tactical nuclear weapons: short-range missiles, artillery rockets, even nuclear torpedoes and depth charges. By 2013 Russia had 2000 tactical nukes in Europe and were building more.

The US ran scenarios about what to do in response to an adversary’s nuclear attack. In 2016 a Deputies Meeting of the National Security Council examined this: the Russians invade one of the Baltic countries; NATO fights back effectively; to reverse the tide, Russia fires a low-yield nuclear weapon at the NATO troops or at a base in Germany where drones, combat planes, and smart bombs were deployed. The question: What do US decision-makers do next?

Vice President Biden’s national security adviser Colin Kahl then stated the answer. The minute the Russian’s drop a nuclear bomb, we would face a world-defining moment — the first time an atom bomb had been in use since 1945. It would be an opportunity to rally the entire world against Russia. If we restricted our response to conventional combat and diplomatic ventures, we could isolate and weaken Russian leaders, policies, and military forces. However, if we respond by shooting off some nukes of our own, we would forfeit that advantage and, more than that, normalize the use of nuclear weapons.

The same exercise was held a month later and the proposed response was we could rally the entire globe against Russia — with sanctions, shutdowns, trade blockades, travel bans: the impact would be more devastating than any tit-for-tat nuclear response. Kinda like what we are seeing right now if you have looked at the news in the past two weeks.16

However, in this session, Ashton Carter, Obama’s fourth secretary of defense, furiously responded that we must meet a nuclear attack with a nuclear response. Otherwise it would be the end of NATO, of all of our alliances, and the end of America’s credibility worldwide. And you know what, the generals agreed with Carter.

Vice President Biden gave a Farewell Speech on January 11th 2017. There is this part of it in particular: “The next administration will put forth its own policies. But, seven years after the Nuclear Posture Review, the President and I strongly believe we have made enough progress that deterring — and, if necessary, retaliating against — a nuclear attack should be the sole purpose of the US nuclear arsenal.”

On July 20th, Trump was briefed on America’s military strength in the Pentagon. Among other things, he angrily questioned why we didn’t have more nukes. The officials explained that the roughly 2,500 nuclear weapons active in the US arsenal were more than adequate to perform the missions suited, and far better than the larger force we had half a century earlier. Trump still wasn’t happy and there was some more back and forth. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson said under his breath, but only loud enough for the people who stayed behind to hear, that the president was a “fucking moron”.

A month or so before this, General James “Mad Dog” Mattis examined arguments for nuclear scenarios. One from his former mentor, Bill Perry, objected to the sponge theory, in which the Soviets would fire 2000 nuclear warheads to destroy the 1000 ICBMs that the US had after refusing to de-escalate from a nuclear deterrent strike launched by the US. First part of this objection: Obama left the White House with only 400 ICBMs and Russia would only need to respond with a couple dozen to be a sufficiently daunting sponge. Second, the US has more than 1000 warheads on submarines at sea. No Russian leader could assume that the American president wouldn’t launch them. Finally, dismiss the premise that the Russians would be eager to launch a nuclear first strike at the United States.

In the following months Mattis assembled a group of advisers, and in a session on November 1st there was another significant development in nuclear strategy. Elbridge Colby, the deputy undersecretary of defense and the grandson of former CIA director William Colby said as much to Mattis: “Mr. Secretary, strategic thinkers of my generation do think there are opportunities to limit nuclear conflict.” Mattis rolled his eyes. General Dunford, the Joint Chiefs of Staff chairman rephrased that: it didn’t matter whether we think nuclear war can be controlled; what mattered was whether the Russians think it can be. Rose Gottemoeller, the NATO deputy and former arms control negotiator, chimed in through a remote link from Brussels: From what she read from CIA and State Department intelligence reports, the Russian officers who wrote the new doctrine, who tested it in exercises, had said explicitly that they would use nuclear weapons—-they would “escalate to de-escalate”--only if NATO invaded their territory, only if the Russian republic was endangered.17

In the end, the generals did appeal to the House Armed Services Committee and the Senate Armed Services Committee in the following months. We needed low-yield warheads. If the Russians fired a low-yield warhead at a NATO ally and the United States lacked low-yield warheads of its own, the president would face a choice of “surrender or suicide”, to quote Henry Kissinger’s phrase.18

And thus the “low-yield” Trident II warhead became the nuclear weapon of choice. The conventional bombs that leveled buildings in Iraq and Afghanistan (and right now in Yemen)19 have an explosive power of 2000 pounds of TNT. The Trident II explodes with 8000 tons, that is 8 kilotons or 16,000,000 pounds, of TNT — plus the heat, smoke, and radiation, that will spread like toxic wildfire. The bomb that hit Hiroshima was 12 kilotons, for reference. Also, the Trident II warhead detonates in two stages: the primary fission weapon, like in Hiroshima, is 8 kilotons. But after that goes off it triggers the secondary fusion implosion which boosts the explosive power to about 150 kilotons.

Where We Are Today

All that I’ve written here is by no means a detailed or exhaustive look at the times a handful of people were ready to blast us all to hell. And there were more incremental changes to the cuts of the nuclear arsenal and it’s tactical purposes, but those were omitted for brevity.

You might be one of those people calling for a no-fly zone over Ukraine. That is a very bad idea. First, as of this writing Russia still hasn’t established air superiority in Ukraine. Second, no air force wants to fly around a country where every third person has a man-portable air-defense system (MANPADS). Third, the enforcement of a no-fly zone means Russian air forces and NATO air forces would be directly fighting each other. Meaning a NATO member and Russia would be shooting each other. Therefore article 5 (war) would be invoked. That means all NATO members would get involved. That means nukes would be used like in the number of scenarios I just wrote this whole essay about.

There is an extremely low chance, if any at all, that Putin will use a nuke on the Ukrainian capitol. That would be a waste of a warhead.

Unlike conventional warfare which is studied and fought, and has available lessons from books and experiences on the battlefield, there are no chronicles, no empirical evidence, of how a nuclear war might unfold.

The important politicians know the stakes and preparations necessary for everything I’ve written here and are weighing them right now. Why do you think some of them look so tired on TV the past few days? Still, we get takes like this

20.

Nuclear exchange is not a good thing. And if it happens it may not wipe out everything. If it happens, and you survive, and the government survives, there is not even the joke of democracy left. It is full martial law and totalitarian rule. Since 1994 with Bill Clinton’s Executive Order 10998, the government can seize horded food supplies from both public and private sources. Since March 2012, Barack Obama’s Executive Order 13603 grants the Department of Homeland Security, the Department of Agriculture, the Department of Labor, the Department of Defense, and other agencies complete control of all US resources, including the ability to seize, confiscate or re-delegate resources, materials, services, and facilities as deemed necessary. That includes all forms of energy and energy production and “food resources”. Lastly, that executive order registers all Americans, similar to the military draft, so that they can be forced to perform jobs and services that the government deems vital.

“As long as others have nuclear weapons, we must maintain some level of these weapons ourselves.”

Potential Nuclear Targets in the Event of a 500 Warhead and 2000 Warhead Scenario. https://i.redd.it/685zwbzllme81.png. Accessed 12 Mar. 2022.

Helfand, Ira, et al. Projected US Casualties and Destruction of US Medical Services From Attacks by Russian Nuclear Forces. p. 9.

Imgur. “Effects of a Full-Scale Nuclear Exchange on the United States.” Imgur, https://i.imgur.com/cIzKj7U.jpg. Accessed 12 Mar. 2022.

Cockburn, Patrick. “Toxic Legacy of US Assault on Fallujah ‘Worse than Hiroshima.’” The Independent, 23 July 2010, https://archive.ph/9tmvD.

Speech of Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, “The Strategy of Massive Retaliation,” Council on Foreign Relations, Jan. 12, 1954.

Bill Kaufmann. Interview with Kaufmann. Interview by Fred Kaplan, 1980.

Kaplan, Fred. “JFK’s First-Strike Plan.” The Atlantic, 19 June 2017, http://archive.ph/AUsWs.

The Presidential Recordings, John F. Kennedy--The Great Crises. Vol. 2 and 3. University of Virginia--Miller Center of Public Affairs.

“Notes on NSC Meeting, 13 Feb. 1969.” Feb. 14, 1969, NSA/EBB No. 173, Document 6.

Reagan, Ronald. Ronald Reagan / An American Life. Pocket Books, 1999.

Butler, George Lee. Uncommon Cause: A Life at Odds with Convention. Outskirts Press, 2016.

(Butler)

Richard Lugar. Interview with Richard Lugar. Interview by Fred Kaplan, 2018.

Plainly Difficult. A Brief History of: The Largest Man Made Explosion (Tsar Bomba). 2018. YouTube,

Department of Defense, "Nuclear Posture Review Report," April 2009, 15.

O’Toole, Brian, and Daniel Fried. “What’s Left to Sanction in Russia? Wallets, Stocks, and Foreign Investments.” Atlantic Council, 9 Mar. 2022, https://archive.ph/6y6UO.

Pellerin, Cheryl. “Mattis Begins Nuclear-Focused Trip.” U.S. Department of Defense, https://archive.ph/JTr7b. Accessed 12 Mar. 2022.

Kheel, Rebecca. “Mattis Defends Plans for New Nuclear Capabilities.” The Hill, 6 Feb. 2018, https://archive.ph/vqFK6.

yemenvoice. “Because Yemen Is Not Ukraine, You Won’t See This in the Media.” R/YemenVoice, 7 Mar. 2022, https://www.reddit.com/r/YemenVoice/comments/t8o5pv/because_yemen_is_not_ukraine_you_wont_see_this_in/.

Josh Wingrove. “Biden Says the U.S. Is Willing to Fight World War III to Defend ‘Every Inch’ of NATO Territory If Attacked by Russia and Putin. ‘Granted, If We Respond, It’s World War III, but We Have a Sacred Obligation’ to Defend NATO, He Says. Https://T.Co/JhvqdWbatB.” @josh_wingrove, 11 Mar. 2022,

https://archive.ph/x1IKA.

Alex Glaser. PLAN A. 2019. YouTube